I am told, I am the first woman to get inside a gold mine in Vihiga county, Kenya.

In many parts of the world, women are not allowed to go anywhere near a mine because it’s believed that mining sites are men’s territories, so women are responsible for removing gold from the soil after the actual mining process. Our Extractives team was on a scoping mission to understand the circumstances that artisanal small scale miners live in. I was the only woman in the team, tagging along to capture these stories on film.

When we got to those dim, dusty mines, we found that women generally operated at the periphery of the mine, processing the leftover ore for a small amount of gold. This, they sell to brokers for about Kshs. 200-300 (USD 2-3), an amount which they use to care for their families. The main ore – large rocks – are taken away in gunny bags by the men who bring them up from the dark shafts, deep in the earth. This bounty is shared between the mine owner and the miners.

Women are kept away from the mine shafts; dark, dusty, claustrophobia-inducing holes that usually go almost a Kilometre into the earth. “It is not safe for a woman to go down there. It is just not done. Let her husband go and fend for the family,” we were told.

“It is not safe for a woman to go down there. It is just not done. Let her husband go and fend for the family”

In Vihiga, I pleaded with the men at the mine to let me go down. I wanted to document the places where they have to work. I wanted to go down to the invisible place, where many men have gone. At length, they agreed, mostly because they were amused that this girl wanted to go deep into men’s territory and that she was not afraid.

To go down, with my camera hanging loosely around my neck, I had to place one foot in a bucket and hold on to the rope as I was lowered into the darkness. It was scary, it was thrilling, but it was worth it.

Filming as a woman

As a member of the Open Institute’s Communications Department, I get to plan, film and edit videos, what we film-geeks call pre-production, production and post-production.

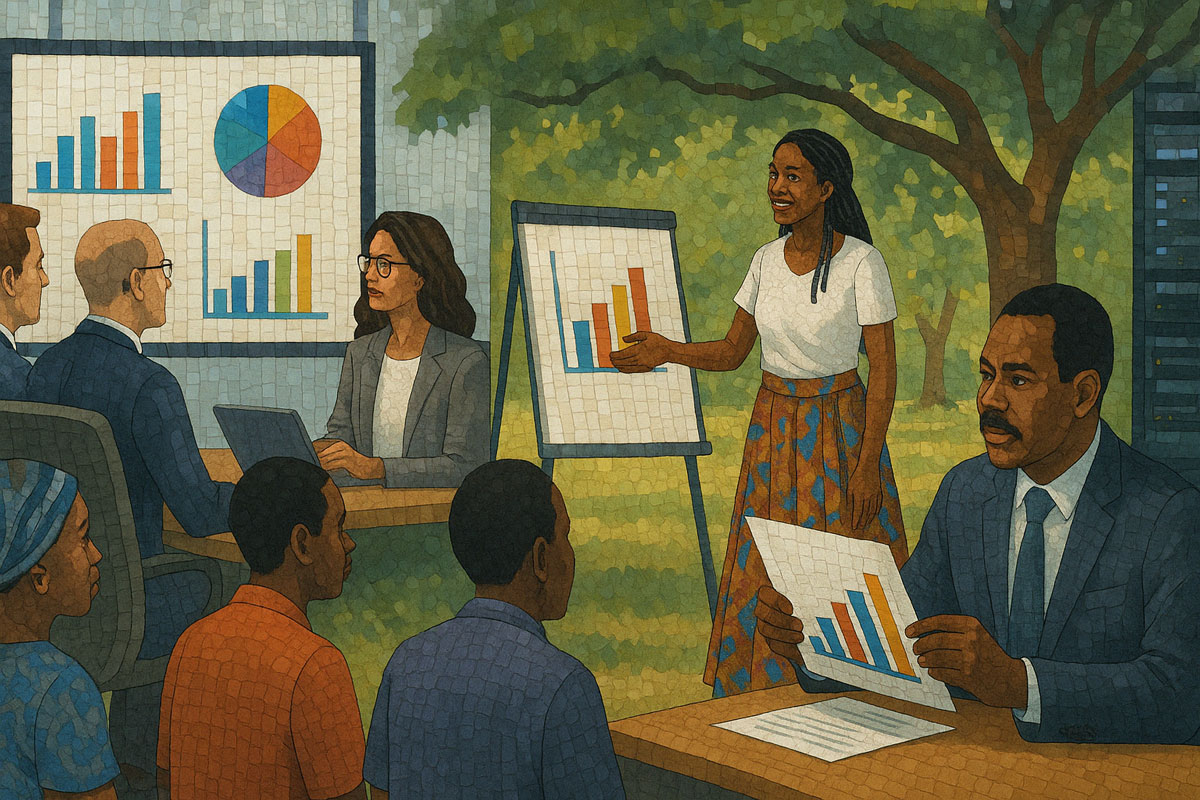

Working at the Open Institute has been one of my most adventurous experiences. I have had the opportunity to travel to all parts of the country and meet new people, visiting places that I never thought existed. Some of the counties that I have enjoyed documenting include Lamu, Mombasa, Kilifi, Taita Taveta and Kisumu. I have come to learn how to prepare and familiarise myself with people, since our projects involve promoting active citizenship while working with the government towards the needs and welfare of their communities. This usually means filming community meetings in dim churches and social halls and often under trees.

In many instances, it is harder and more perilous for me as a woman

Prolyne Nancie, Communications Officer

In many instances, however, it is harder and more perilous for me as a woman. Take Migori, another mining community, for example. I walked into their largest mine to find more than 2000 sweating, dusty muscular men, jostling to measure the gold they had just brought up to the surface after 24 hours in the mine. I had to photograph this. I walked into that space, jostling with them as I tried to pass, stepping on gunny bags filled with precious rocks. I had to climb onto a rafter to get a vantage point to film this cacophony, much to their amusement. Many catcalled and threw sexual epithets at me and at one point, my team had to escort me out of there for my safety.

In Taita Taveta county, the team wanted to speak to the miners and understand what challenges they encountered, finding out if they had proper working gear in order to find a way to influence the development of policies to protect them and improve their working conditions. However, to my surprise we were not allowed to document anything; the miners were very strict and super aggressive when it came to their photos being taken even after politely requesting for their consent.

Finding the story

My work mainly involves finding the story and it then requires me to be very curious; to ask questions, sometimes doggedly, until I can get an answer. The process for me usually involves preparation, where I learn all I can about the people we shall meet and figuring out the questions that I could ask.

It also needs me to be aware of the voices in the periphery. Very often the best stories that I have found have been told by people who were on the sidelines of the activity we were filming. When we interview them, they tell stories that we sometimes had not anticipated.

Things I have learnt over time

- It can be a bit lonely

Working while travelling is fun but it also comes with its challenges. Most times, I have found myself travelling alone among men during our community engagements programs in the field. Having a great rapport with the team helps.

- It can get exhausting

Field work is also quite taxing and can be exhausting. After a long day of documenting and interacting with the people in different locations, exhaustion can get the better of you. Often you have to lug a lot of equipment with you. In one interview we had to do a few years ago in Nakuru, we needed to go to the interviewee’s house. “It is just over here,” she said. We had to carry heavy lights and cameras for kilometres to the house. If we had known, we’d have driven there but because she is used to walking, it wasn’t far from her perspective.

- The team matters

As a team, over time, during the community engagement programs we have developed a culture of waking each other before 6am to help prepare for the day. One team member is tasked to call everyone and knock on the doors of those who are still asleep to avoid leaving anyone behind. Our team is usually considerate of me, helping me as I need the help but leaving me the freedom to do my thing.

- Prepare, prepare, prepare

Preparation is vital. I am keen to organise myself before I travel, putting together shooting scripts, which trigger great responses during interviews, familiarising myself with the place we are going to be filming in and the main actors. It helps to visualise what the story might look like at the end – sometimes, the story is going to be different from what you expect but it helps to prepare.

- Keep an open mind

When I go to the field, I never know what to expect. Even with all the preparation, I have to be ready to adapt to changing circumstances and go with the flow. We once went to Kasighau, in Taita Taveta County. There, we had intentions to film artisanal small scale miners talking about the challenges they have to go through. When we got there, they were firmly against any filming – so much so that they strictly supervised our stowing the equipment back in the car, along with our phones. It also is important that I am always on the lookout for the next big shot. My rule is, capture as much as you can, this comes in handy during the post-production phase.

Must-haves

Our logistics team organises everything we need, from tools to accommodation, transport and any materials needed to make work easier during travels and at the office. Some of the things that are a must-have for me are:

- Camera and Lenses

- Batteries and chargers

- Lapel Sound microphones

- A Hard Drive

- Memory cards

- Card reader

- Tripod

- My Laptop

- My phone and charger

WORDS I LIVE BY:

“Create your own visual style…

let it be unique for yourself and yet identifiable to others.”

Orson Welles