In November last year, as the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education exams were being held, we released data that we have collected relating to primary (or elementary in some countries) school education in Kenya. Through KCPE Trends, we released KCPE results data with the view of stimulating conversations about education standards in Kenya. In doing so, we prompted Kenyans to review the performance of their primary school alma mater over five or so years and we asked them if they would take their children to the same primary schools that they went to.

The reactions were illuminating – first, most people said that they wouldn’t and were appalled by the declining standards. People from the Coastal counties of Kenya (where people are native Swahili Speakers) were perplexed by the fact that their schools performed worse in Swahili subject than schools in Central province (whose tongues struggle with proper Swahili).

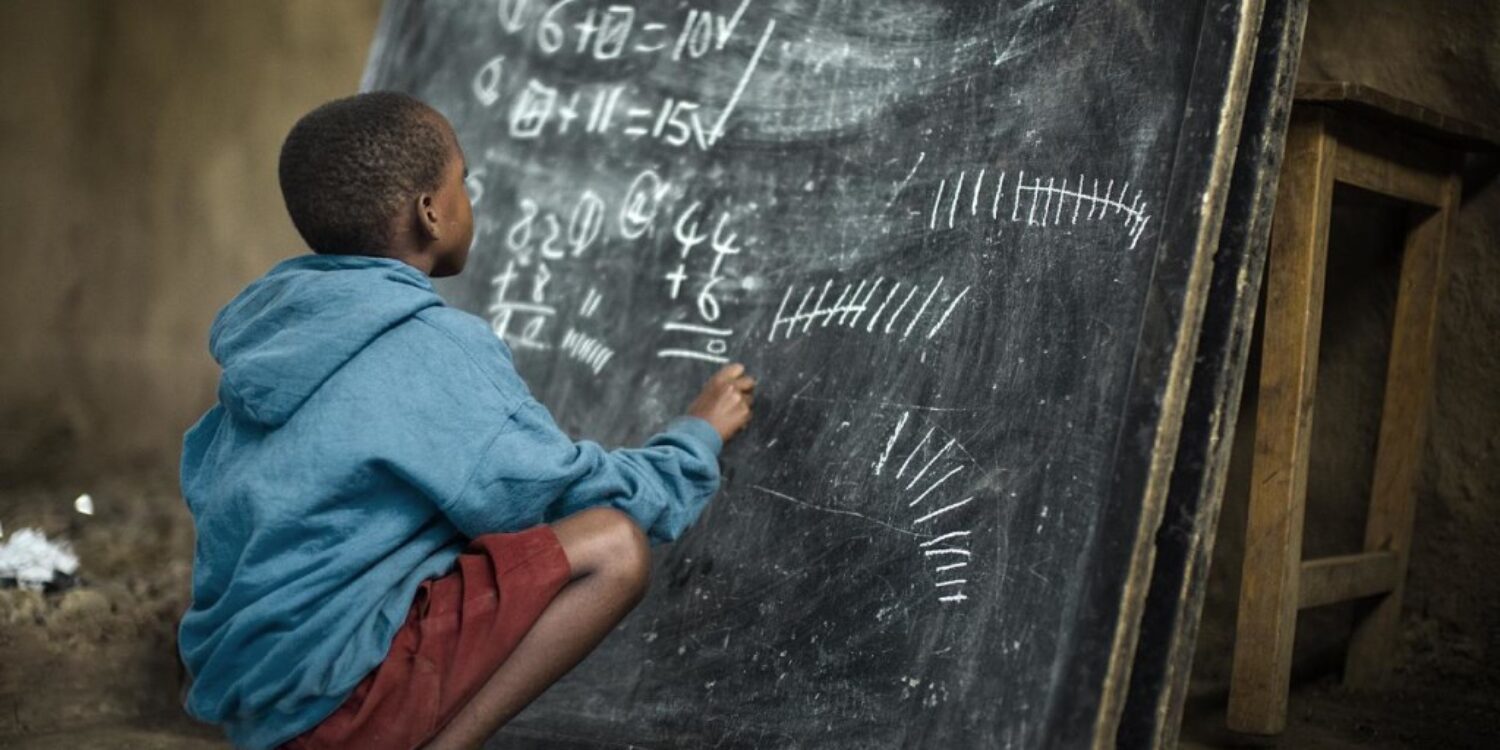

But it went further and deeper. Many decried the declining physical state of schools and the fact that teachers in Kenya are not well paid and trained. Some wondered to what extent teaching was a calling and not just a job. There were robust discussions about parenting and the relationship between parental responsibilities and discipline. There was wide spread scepticism about the government’s laptop project and whether it was a priority in a county where many children still go to school under a tree, seated on the dirt floor. There was sardonic commentary about the emerging texting culture “After LOL was added to the dictionary, curious to see this years National English average grade”. People wondered whether there wasn’t a fundamental problem with the entire education system and whether we shouldn’t just chuck it out wholesale and start on a clean slate.

The reality of life is that on the subject of education, everybody has a strong and often valid opinion.

On each of the above topics there is held passionate views on multiple sides. It is a noisy and emotive room, where education is discussed. We should know – we held a stakeholder’s roundtable on the subject. Not only did the discussions go woefully over time, but it was also apparent that even had we spent three days, we would not even fully agree on what the problem with education is and what must be fixed to make it progressive and better.

Unfortunately, time doesn’t stand still. The statistics on education are growing grimmer by the year. See this from a UNESCO fact sheet:

And then see the 2013 report by Uwezo East Africa at Twaweza, whose annual report has become an important barometre in the East African region of what the state of education is and your heart plummets even further. Things are getting worse.

And then see the 2013 report by Uwezo East Africa at Twaweza, whose annual report has become an important barometre in the East African region of what the state of education is and your heart plummets even further. Things are getting worse.

We, at the Open Institute, have been preoccupied with one question among several and it is one that has somewhat taken pre-eminence in the thinking around our education programme: What is the problem with education in Kenya? in East Africa? In Africa?

When you speak to the teachers union, you hear that the real problem is that teachers are not motivated enough through pay and benefits. When you speak to head teachers you hear that schools have barely enough funding to maintain classrooms and water facilities – let alone build them.

When you speak to parents, you hear that the education system is dubious, that it has undergone too many patchwork changes for it to be relevant. “How can my child be competitive in this world when technology is not taught in school?” an iPad wielding middle class parent asks.

Yet another parent in a remote county wants to know how his child could have a hope of being literate (forget competitive), if there are only two teachers in an area of 100 square kilometres. And in the same area a mother wants to know how we expect her daughter to become a teacher if she cannot stay in school because it has no sanitary facilities.

You speak to a policy maker and you hear pontification about how parents have abdicated their responsibilities to their children as they chase their daily bread. “When we were young,” the commentary would begin, “our parents were there to teach us values, to spank us right along side the teachers when we misbehaved. There was a tightly woven net between teachers who taught academic things and parents, who taught values and morals. Now all of it is left to teachers.” There are not enough hours in the day to teach arts and music as well as religion and morals (the latter of which are examinable subjects in Kenya), the policy maker continues. “We have to prioritise.”

Even in the civil society, the voices are many and they too go in all of these directions depending on their areas of focus.

All this while, 5-year-old children are up at 5am to trek many kilometres to school in rural areas or to brave the traffic jam, when they live in the city. Employers are lamenting that many of the “learned” employees that they employ have no social or life skills and struggle with leadership and problem solving.

(All of these comments are true comments that we have received as we went around asking the question, “what is the problem with education” in the past 6 or so months).

One cannot help but sympathise with the President and his cabinet secretary for Education. Unlike other sectors that may be relatively easier to develop a prioritised checklist (e.g. Agriculture: seeds for farmers, fertiliser, water facilities, extension services, storage facilities, markets for produce…), education is harder to develop a prioritised checklist for.

So the question we are asking ourselves, and we would love to hear from you is this: If we as a society were to attempt to develop a prioritised checklist of all of the problems that bedevil the education sector, to study all of the issues / problems and have one checklist that is listed in order of priority, how would we go about it? How could such an initiative be structured?

Imagine if the president has a list of that kind. Wouldn’t he do better where education is concerned?

Not doing this is for us not an option. The essential question is how?