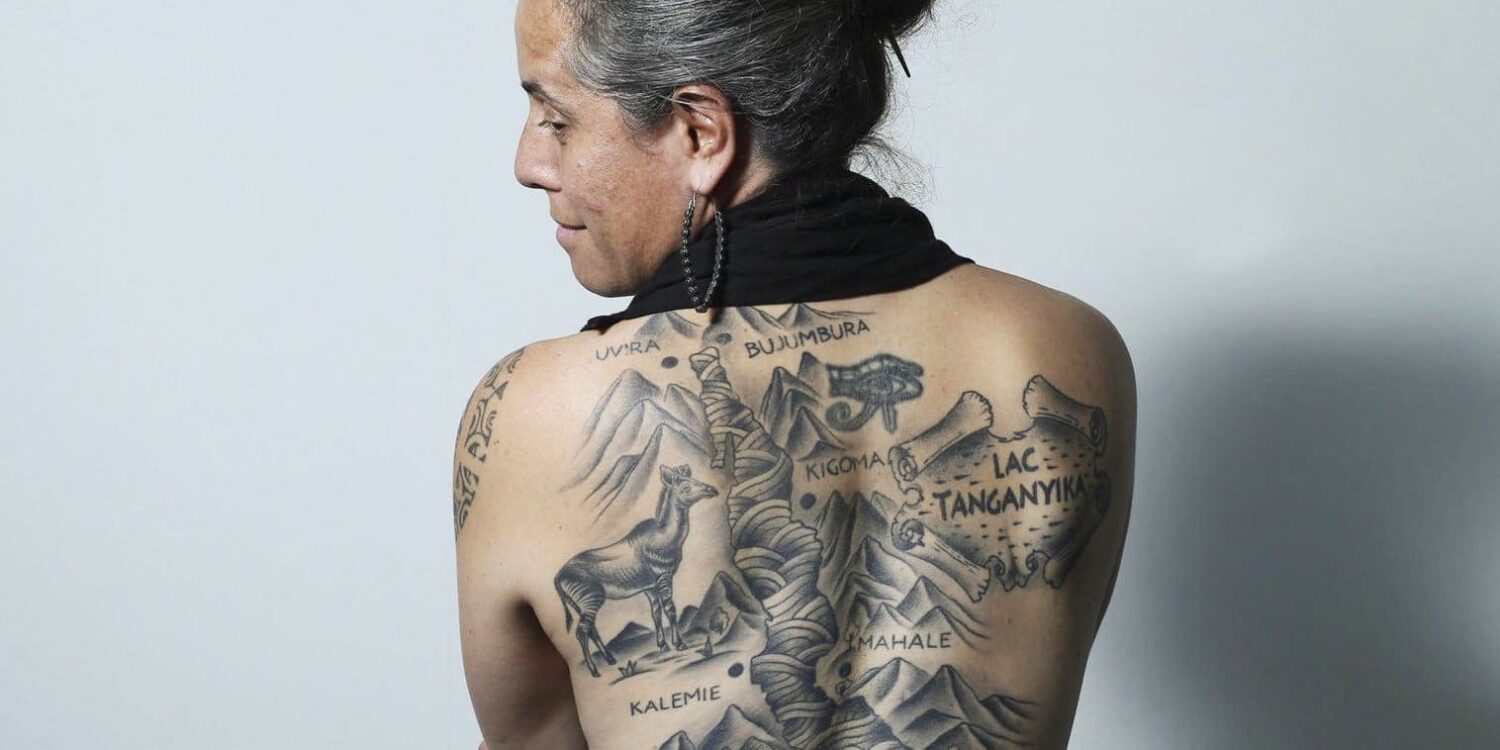

She bagged both an MD and an MBA from the University of Chicago. Trained in General Surgery at the University of Chicago Medical Center. A former Senior Fellow with the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics. Honoured by Newsweek as one of the “150 Women Who Shake the World,” among other accolades, Dr Amy Lehman is a force to reckon with. She is the founder of the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic. LTFHC is an international organisation whose mission is to address healthcare access and education for isolated communities in the Lake Tanganyika Basin/Great Lakes region in Central Africa.

The floating clinic idea was born by chance. Dr. Lehman was travelling around Lake Tanganyika, a place that has always fascinated her and while there, a typhoon caused the airstrip to be washed away. They ended up stuck! She got the opportunity to traverse the coastline. She realised that a large population living around the lake’s shores, in parts of the Congo, Burundi and Western Tanzania, was utterly cut off from the rest of the world. The transport systems were inadequate, and there were significant supply chain issues.

These residents in the area were primarily refugees and internally displaced people who had suffered through wars, political upheaval and 20+ years of non-stop instability. The socioeconomic and public health indicators were terrible. She realised that better infrastructure and better access to basic healthcare would make a big difference. Since the only way to reach them was via boat, the idea of a floating clinic was hatched, and this is how the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic (LTHFC) was born.

We had a virtual sit down with Amy to discuss LTFHC 12 years on; this is what she had to say.

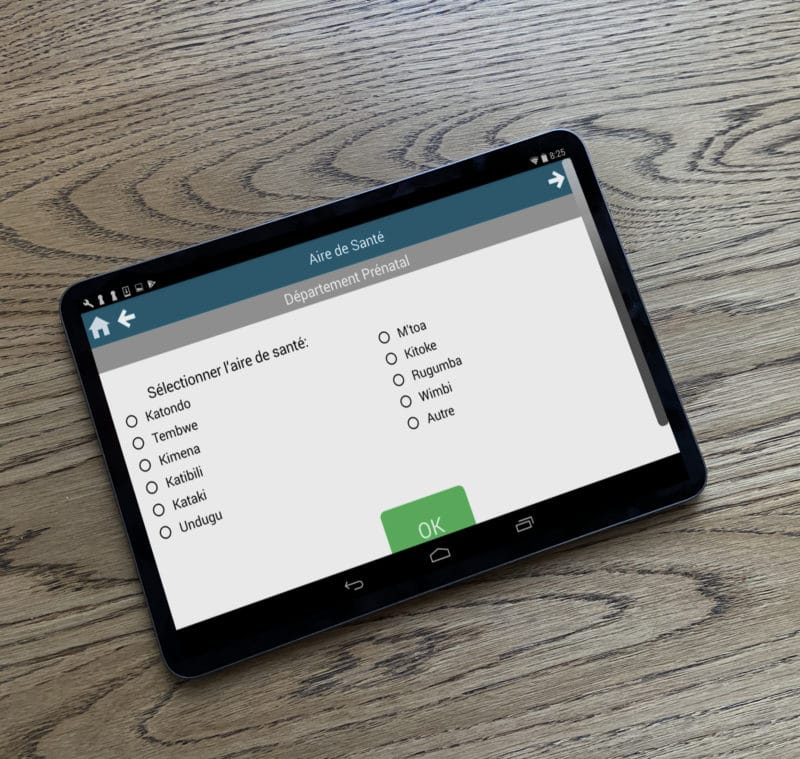

- Tell us about your organisation, how you began and how you got here. How has the journey been to date? It has been 12 years since LTFHC was born. When we Started, the clinics in DRC used the paper record system to note down all patients records, from their name to their ailments. It would then be transported to the health zone and logged into the DHS, the central health record system. This was not viable as most of the intrinsic data got lost. We started looking for potential off the shelf products that could store the data. This is where the Iroko App comes in. Its user interface mimics all the paper steps that the health workers were conversant with and is recognisable to the health workers and easier to use. The journey according to Amy has not been easy, but the impact of the LTFHC work has been worth it, and for that, I cannot complain,” she says as she l

- Talk about some of the programmes and activities is the LTFHC focused on currently. Currently, we are working on finishing the app (Iroko Health) and working on a scaling strategy in different health zones across DRC. We are also working on addressing the community data problem as it is fundamental in managing all the other issues in the area. The other major programme is in partnership with the business school at the University of Chicago (The Booth School of Business). We are working on a supply chain model for really hard to reach communities by using our community-level data sets to create a model about how we might be able to bring a certain type of products into these communities, as this hasn’t been feasible before.

Data should be an all-inclusive conversation and not an elite conversation. This is because the intrinsic data that needs to drive change comes from the communities. It comes from the grassroots, not from a pack of elite individuals

Dr Amy Lehman

- Iroko Health, a health app that you pioneered and that captures community-level health data in the DRC, has done remarkably well, and there are plans to scale it. Please take us through the app and the possible features that you hope to add to it.

In the making of the app, we took a very humble approach. We went back to the ground and worked with health care workers in the field and tried to understand how they did their documentation. Then we created a prototype which we sent back to them. From this, we got what was liked and what wasn’t; this practice also enabled them to guide us on what was needed to solve their issues, which is how Iroko Health was born. The idea was to recreate a system that had been in existence in the country for more than 50 years instead of replacing it; a tool that the local health care workers would adapt to efficiently as it has the same features as the system they were conversant with before.

- What are some of the blindspots that technology can fill in health care, and what role do you see technology playing in improving healthcare in Subsaharan Africa? It is important to recognise that there is profound heterogeneity in different countries and continents all together; hence the technology interventions deployed in these areas need to speak to this diversity. An example is DRC, which has one of the lowest mobile connectivity in the continent, unlike Kenya. With the issues in DRC in mind, we ensured that a feature of the Iroko App wouldn’t rely on mobile phone connectivity, neither would it need electricity. Instead, we use solar charging units, which are being installed in health centres. This provides the electricity needed to power the tablets used in the different health zones. The app can also grab information from one tablet to the other using Bluetooth. I will finish by saying, technology is a driving force for healthcare in the continent and the world as a whole, as long as the homogeneity between regions is recognised and tools tailored to the differences in scenarios.

- Recently in Congo, the government launched a new branch of the Ministry of Health devoted to thinking about digital infrastructure and tools (whose acronym is ANICiiS) Could you shed some light on the collaboration that LTHFC has with ANICiiS and the progress made so far? I was excited about ANICiis from its creation until it became operational, as the issue of efficient data flow has plagued us since the beginning. For an agency to be created by the Ministry of Health and devoted to data flow and proper data management, it is an excellent development in health care data in the DRC. So far, the collaboration has been incredibly productive and very gratifying for us at the LTFHC. It does feel good to be recognised as competent within the constraints of the environments we have had to confront for this kind of community health data problem. Even though the approach that we took was long and arduous, it was for a good course. Just like with many agencies in most African countries, ANICiis requires outside funding. My main goal in this collaboration is to ensure that funders who are interested in big structural steps in addressing the community data gap issue are aware that the DRC has this branch (ANICiiS) and that it needs financial support.

- Like any non-profit organisation, funding is always a topic of discussion. How does the LTFHC get funded? At the LTHFC, we receive funding from small family foundations and some high net worth individuals, among other pockets of private funders.

- How do you measure the impact of LTHFC in the Lake Tanganyika region? It’s important to recognise that different metrics should be used to measure different impacts. In most projects, we tend to choose what it is that we would like to measure before initiating the project. However, whilst performing experiments, we learn about different variables, potential outcomes, among other things, hence the metric changes. Using the app as an example, we would have a moving and evolving set of impact targets:

Step 1: Expand the accessibility of the app across a certain number of health areas and health zones where health care workers effectively learn how to use the app and adopt it, then convert them from using pen and paper with this electronic version to a point where significant data flow is seen.

Step 2: This would involve accuracy. Is the data flow accurate? Are people entering data correctly? Can health workers be cued to respond to certain questions from patients in a proper manner? These are our metrics at the moment. The approach is very experimental. We are allowing ourselves to crawl before we can walk without a chance of recidivism.

(image credit)

- How has COVID-19 affected your work in Lake Tanganyika, and how are you and LTHFC managing this situation? It was very difficult. We weren’t able to go to the field, neither could we travel back and forth. However, the silver lining was that we were better positioned to figure out how to continue being productive because of the vast experience working in a fragile and uncertain environment. The novel Coronavirus presented several challenges. That mindset of flexibility that my team at the LTHFC has always had is one that we have always had to work in the environment where we operate, making it easier to maneuver Covid-19 and the uncertain times that we are all existing in.

COVID taught us several things but most importantly, it taught us to do the data right. Data is the key to understanding what’s happening today and the things that we hope to perform in the future. All this, however, is down-up; it comes from the communities. If you want to track anything from COVID-19 to malaria, then you need to have the community data. This is the most up-strain vital capacity that we need to build on.

Dr Amy Lehman

- What are the next steps for LTHFC? We are currently going down the homestretch with kind of finishing the app in its totality. We are almost done with all the related clinical data. We are presently handling the last bit: the administrative related data collected at the healthcare level, i.e. inventory management, HR registers, and fees that are collected at the health centre level. We are also looking to technical people in the national Ministry of Health about making sure that we have the most up to date paper forms. Secondly, we are working to identify collaborators at the national level that allows us to ask deep questions, in order to understand what inquiries are being made; what is being captured in the report? What is the datum? How does it code into the report? What are the actual set steps and set of thinking that goes into each of the forms? All this is keeping us occupied at the moment.

- What has been the greatest lesson learnt in the 12 years that you have been in operation? The greatest thing that I have learnt is to be humble until you test what you know; until you have rigorous and objective material and experience, don’t project. Don’t think that your expertise and methodology in one context can be applied in another context because this is not the case. Listen, observe, and experience what’s in front of you and for a while, only then can you begin to problem solve.

For Amy and the greater LTHFC team, their driving mission is to make data sets more accurate and reflective of heterogeneity in the community. This informs everything from policymaking to the distribution of resources in the different regions.

Find out more about the floating health clinic and the important work being done by their organisation.