What happens when people are invisible in the numbers? When communities are omitted from datasets that shape national policy? When stories that are rich, complex, urgent are reduced to a footnote or not recorded at all?

In Kenya, where 2.2% of the population — over 1 million people — are recorded as having a disability, we still know too little about their lived experiences. Even more striking: 57% of them are women, and yet, the data systems that shape service delivery and policymaking rarely reflect their unique realities.

Here, as in many parts of the world, the consequences are tangible: children locked out of schools for lacking a birth certificate; autistic young adults forgotten by systems that cater only to minors; men suffering silently because masculinity norms stigmatize help-seeking; older people excluded from planning because they are not “economically active.” These are everyday realities, and they point to a powerful truth: inclusive data is not about charity; it’s about justice.

This is why the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (GPSDD) is partnering with organisations such as ours to make Inclusive Data the Norm.

In a recent national assessment we conducted as part of the project, stakeholders across Kenya’s data ecosystem spoke to these nuances. Civil society actors voiced frustration with rigid government data tools that exclude community-generated insights. Government officers highlighted structural limitations: a lack of tools to capture invisible disabilities, narrow gender definitions, outdated frameworks that sideline intersectionality.

We saw the need to co-create an inclusive data workshop, which was held in May 2025, in order to ensure that this work is shaped by those it’s meant to serve. The 3-day workshop brought together Organisations of Persons with Disability (OPDs) and data experts to co-create a path forward.

Beyond Disaggregation: Seeing the Whole Picture

Inclusive data is often misunderstood as a call to simply disaggregate by gender, age, disability, geography. But disaggregation is only the entry point. True inclusion in data systems demands that we ask harder questions: Whose lives are not reflected in the numbers? Who decides what to collect, and why? What lived experiences are deemed irrelevant or too complicated to code?

Current data often fails to represent the intersectional experiences of persons with disabilities. For instance, a 2024 UNFPA study highlighted that even when data is collected, it rarely captures the realities of disabled women facing intimate partner violence. Even more, most official statistics focus on functional impairments alone. What’s missing is context: access to education, healthcare, employment, or even safety. And the challenge is deeper in marginalized communities, where stigma, limited access to assistive technology, and geographic isolation compound invisibility.

Without disaggregated, nuanced data, these stories are invisible — and so are the solutions.

Capturing Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a concept often name-dropped but rarely integrated into data collection. An activity during the workshop, where we played a card game we named “Shuffled Identities”, prompted the people in the room to agree or disagree with statements such as:

- “I’ve been interrupted in meetings because of my age, gender, or education level.”

- “My rural or urban upbringing affected my access to extracurriculars or advanced classes.”

These prompts sparked deep reflection and candid sharing. Many participants resonated with the age-related question, leading to an important conversation on how older persons are often invisible in data and excluded from program design.

Data can also mask cultural pressures. One card read:

“I’ve avoided seeking medical or financial help due to the stigma tied to my gender.”

Many men in the room nodded. Some shared that societal expectations to “be strong” have kept them from going to hospitals even when unwell. Others admitted to hiding unemployment or financial struggles. These choices, shaped by deeply ingrained ideas of masculinity, may not show up in surveys or censuses, but they shape everything: health outcomes, suicide rates, economic participation.

If intersectionality acknowledges that people hold multiple, overlapping identities, inclusive data systems must learn to capture silence, not just speech; reluctance, not just participation.

Data Gaps with Real-World Consequences

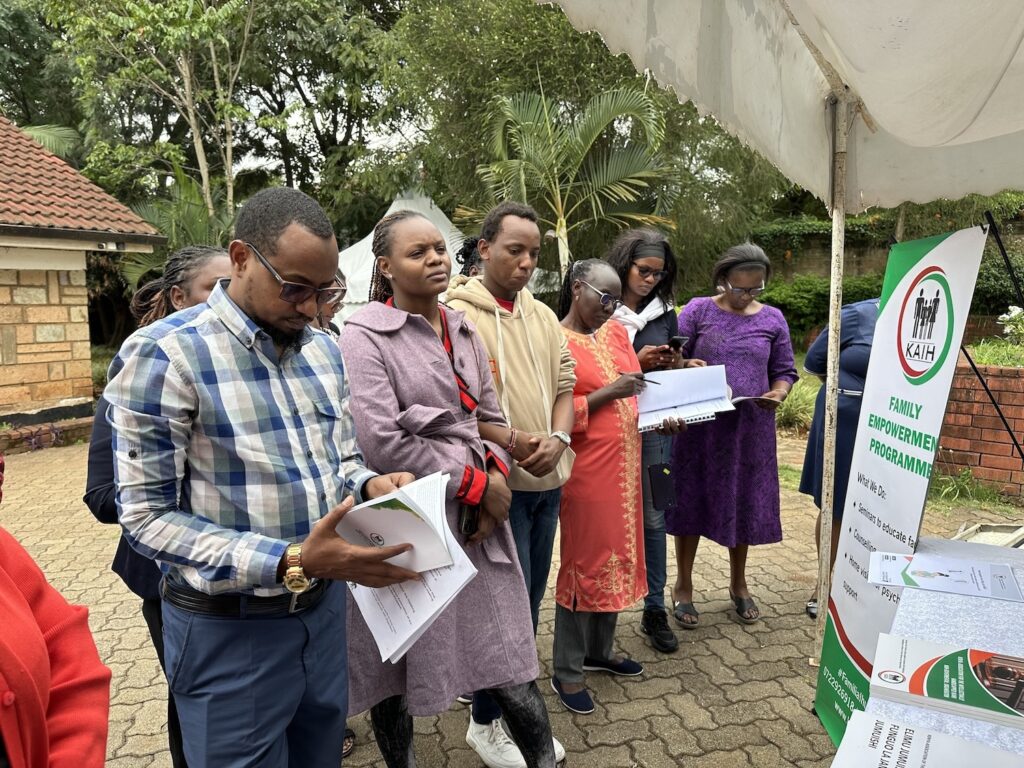

On the third day, we undertook a field visit to Black Albinism, an organisation advocating for rights of people living with albinism. Participants were able to interact with the work of other organisations such as Kenya Association of the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH), United Disabled Persons of Kenya (UDPK) and Differently Talented Society of Kenya (DTSK). From accessibility audits to data mapping, the fieldwork revealed both the challenges and opportunities in developing inclusive, community-owned data systems, helping us to better understand how community-generated data can fill the gaps that official systems often miss — particularly when it comes to persons with disabilities.

The Kenya Association of the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH), presented their robust member data, a rare dataset mapping children and adults with intellectual disabilities across the country. What stood out was that a staggering number of members lacked basic documentation—no birth certificates, no IDs. Without these, you can’t register for school, access government services, or get employment. You don’t exist in the eyes of the system. This presents a form of structural exclusion that begins at birth and deepens with time.

The Differently Talented Society of Kenya (DTSK), led by mothers of autistic children, raised an often-ignored reality: most disability services in Kenya cut off at age 18. Once autistic individuals become adults, support disappears. There’s no transitional care, no employment pathways, no health access designed for them. They simply fall through the cracks.

And yet, they are still absent from most government datasets. Without data, there is no policy. Without policy, there is no funding. And without funding, there is no future.

Inclusion Starts with Curiosity, Not Checklists

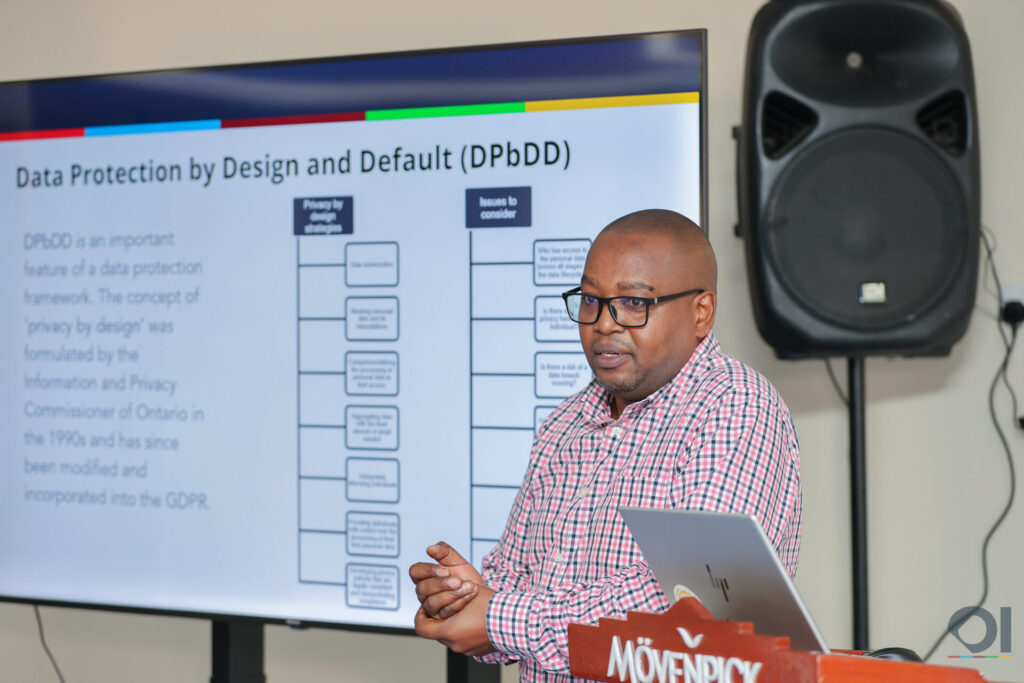

Through conversations grounded in frameworks like the Copenhagen Framework and Kenya’s KeSQAF, citizen-generated data (CGD) can complement official statistics and help tell richer stories, especially when it comes from the communities themselves.

One of the most powerful takeaways from the field conversations was that inclusion can’t be tokenised. It’s not about inviting someone with a disability to an event or adding an “other” option on a form. It starts with listening without assumptions, asking better questions, and building data systems that adapt to complexity rather than flatten it.

The United Disabled Persons of Kenya (UDPK) put it best during their session: “Inclusion isn’t a favor. It’s a responsibility. Ask what accommodations people need. Don’t assume.”

Systems That Leave No One Behind

Government actors at the workshop shared encouraging signs of progress. The Ministry of Social Protection acknowledged its role in championing visibility, particularly for older persons and persons living with disabilities. The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics presented its guidelines for citizen generated data, which outlines criteria for inclusion of this data into national statistics.

Still, the road ahead is long. There is a need to shift from fragmented pilot efforts to systemic change. This includes embedding inclusive data practices in national statistical strategies, investing in community-led data generation, training duty bearers, and designing data systems that value nuance over neatness.

The Path Forward: Inclusion as a Practice, Not a Promise

Over the course of three days, it became evident that inclusive data is about seeing, hearing, and valuing the people behind the numbers.

The workshop may have ended, but the work is just beginning. At Open Institute and GPSDD, we’re committed to taking this energy forward—refining the training module; supporting organizations to integrate inclusive data practices; and amplifying the voices that so often go unheard.

Together, we can build systems that do more than count people; let’s build systems that see them.

This reflection emerges from the Open Institute’s collaboration with the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data as part of the “Making Inclusive Data the Norm” initiative. The inclusive data workshop brought together civil society, government, and grassroots organisations to co-create solutions for Kenya’s data future.